Caergenog — just across the Welsh side of the border with England — was populated by a few hundred souls, a village demarcated for centuries by two pubs, one at the top of Roberts Road and the other at its foot. The high ground belonged to the Butcher’s Hook, named in recognition of the weekly livestock market across the street, while the low ground, opposite the church and roundabout, was occupied by World’s End, a reference to that pub’s location at the outer boundary of the village. World’s End had always been the less popular option (who wanted to carouse with a view of iron crosses in the graveyard?) and the pub closed for good in the late 1970s. The building stood empty for years, boarded up and vandalized, until a married couple — retired academics from the University of Bristol — bought the property and converted it into a used bookshop.

That business plan failed, but Tooly has resurrected it, alas with no positive results to date. As the previous owners said, maybe “some youthful energy” could turn it into a break-even business “but you won’t get rich”.

Tooly intended to walk the entirety of New York, every passable street in the five boroughs. After several weeks, she had pen lines radiating like blue veins from her home in the separatist republic of Brooklyn into the breakaway nations of Manhattan, Queens, and the Bronx, although their surly neighbor, Staten Island, remained unmarked. Initially, she had chosen neighborhoods to explore by their alluring names: Vinegar Hill and Plum Beach, Breezy Point and Utopia, Throggs Neck and Spuyten Duyvil, Alphabet City and Turtle Bay. But the more enticing a place sounded the more ordinary it proved — not as a rule, but as a distinct tendency.

This Tooly has discovered a tactic that helps fuel her curiosity: if she knocks on a door and says she used to live in this very apartment and wants a look round to remind her, people tend to let her in. This thread of the story acquires momentum when she does just that at a suite occupied by three students near Columbia University and moves into their convoluted lives.

“Landing cards,” Paul said, thinking aloud, and grabbed two as they waited in line at the border control. “When were you born?”

“You know that.”

“I know that,” he acknowledged, filling it in. He looked around, startled at the slightest noise — he was rigidly tense in public with Tooly. A Velcro strap on his shoe had come unstuck, so she knelt to attach it. “What are you doing?” he asked irritably. “It’s nearly our turn.”

The immigration officer summoned them. Paul was a man who followed rules — indeed, their absence unnerved him. Yet whenever he addressed authorities his mouth became audibly dry. “Good morning. Evening,” he said, sweat budding on his upper lip.

We know from the other two threads (where Paul is absent) that Tooly got away from Thailand. We don’t know how, and that will become the dramatic dilemma of the novel.

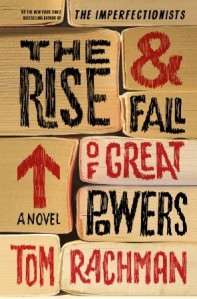

For this reader, The Rise and Fall of Great Powers is the latest example of a new fiction phenomenon (I’m reluctant to call it a genre): authors who have been “raised globally” bringing that experience to their writing.

Now authors have always travelled: Byron and Shelley headed to Italy; Fitzgerald, Baldwin, Hemmingway and a host of others Paris. But that used to happen after they started writing — now we see young (or at least youngish) authors, most of them currently based around New York it seems, producing “globally wandering” novels that capture their growing-up life. From just the last year, I’d give you Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries and Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers. That’s a Pulitzer winner, a Booker winner and a New York Times 10 best, so you can hardly say the trend isn’t attracting attention.

Rachman fits the profile: born in London (the English one), raised in Vancouver, attended the University of Toronto and Columbia in New York, headed off to Europe where he worked for the Associated Press in Rome and Paris. Indeed, his first work — the delightful The Imperfectionists — is a novel-in-stories that I absolutely loved centred on an English-language newspaper published in Rome.

I only wish that I could say the same about this novel. Given that the 10-year-old Tooly stream is mainly a set up, I didn’t expect much from it.

But 20-year-old Tooly in New York as the millennium comes to an end seemed to be fertile ground and 31-year-old Tooly running a used bookshop in Wales sure had promise — promise that kept looming on the horizon but never arrived.

Part of the problem for me was the supporting cast. To keep his story together, Rachman needs to have “Tooly manipulators” and he never succeeded in making them three-dimensional — instead, they became plot advancers. And while I was quite willing to engage with Tooly herself (and often did), bouncing between the decades often left me more frustrated than satisfied. I should confess I had the same problem with Tartt and Kushner’s novels — maybe I am just a reader who wants more “stay at home” depth and less “wandering the world” panorama.

Please don’t let that grumpy response put you off the novel. Rachman is a very talented wordsmith and some of the set pieces in this one are delightful — given my more positive response to The Perfectionists, it is easy to say that at this stage in his career the short story model remains his strength. While I don’t think The Rise and Fall of Great Powers succeeds, it is a step in the right direction — I am pretty sure that sometime in the future Rachman will produce a truly outstanding novel.

July 30, 2014 at 5:15 pm |

Not being much of a global wanderer my self, I probably prefer the writers who stay in one place like Alice Munro, although I did like ‘The Flamethrowers’ by Rachel Kushner as well as ‘The Imperfectionists’. Let’s just say that global wandering does not necessarily a better novel make.

That said, I’m headed for a one week vacation in Nova Scotia. .

LikeLike

July 30, 2014 at 5:49 pm |

Tony: Have a great time in Nova Scotia — it was one of our favorite vacation spots before my back issues restricted my travel. Good friends of ours owned a cottage between Chester and Mahone Bay — we know that part of N.S. quite well.

I quite liked Tooly in New York — liked her in Wales even more. My problem was the every time the author got her “settled” for a chapter, we headed off somewhere else.

LikeLike

August 12, 2014 at 11:06 am |

I’m still tempted by the Kushner, this I’m not so sure. Like you I loved The Perfectionists, but I didn’t like his short/novella The Bathtub Spy (review at mine if you’ve not seen it Kevin) and I suspect I’d like this more if it focused on one strand. Do the three strands eventually interconnect I assume (beyond just being the same person’s life)?

LikeLike

August 12, 2014 at 11:11 am |

They did connect, sort of — not very well, from my point of view. There is a structural similarity with both The Goldfinch and The Flamethrowers (less so with The Luminaries). For what it is worth, I’d put both the Tartt and Kushner ahead of this one.

LikeLike