I have also long been intrigued by similarities between the literature of my Canadian frontier home and the Australian version on the other side of the globe (in the early days of the blog I expanded on this with some examples of comparable works in an essay here). On that Antipodean front, I was introduced earlier this year to the work of Australian Alex Miller with his 2012 novel, Autumn Laing, and impressed enough that I resolved to read his entire back catalogue, in order.

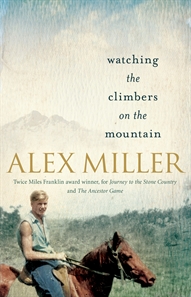

Watching The Climbers On The Mountain (1988) is book one in that nine book project and, while it is not one of his prize winners, it is a frontier story of the first order — more than worthy of comparison with my North American favorites.

One of the traits that all these novels have in common (and it is a reflection of reality) is that frontiers attract misfits, people with serious character flaws or challenges that make them unhappy denizens of the “settled” world, eager to find a new home in a world where “order” has not yet acquired a formal definition that makes them uncomfortable. Miller’s excellent debut novel, set in the Central Highlands of Queensland, revolves around three such misfits:

At fifty-sx Ward Rankin was a disappointed man and was easily aroused to extremes of irritation and even — especially in his dealings with the animals — to outbursts of violence. But he was not predictable in this and could be gracious, even charming, so that his family treated him with caution, forever hoping for the best. He stayed indoors as much as possible and loathed the work of the station, doing the minimum needed to keep the place going. He was a short brittle man, nervous, well-read, priding himself on his civilised habits. An only son, for many years he had managed the property for his aged mother. It was not what he had intended for himself.

Ward is a collector of “brown stamps” — when someone, or the world, treats him like crap, he feels it gives him the right to treat someone less powerful than himself (even an animal) with even greater cruelty.

Ward was forty-one by the time his mother died. A year or two before this he had married Ida Sturgiss, a girl from a neighboring station who had volunteered to help out. She was eighteen. A few months later their first child, Janet, was born. Eighteen months after Janet came Alistair. Ward Rankin never got away from the station and with time he grew to resent the circumstances that bound him to it.

Ida’s resentment over her lost chances is every bit as deep.

At first they teased him about his shyness but soon recognized that it was something more than this. There was a closed solitariness about him that was not natural in a young man. He brought this solitariness with him. It was deeper than theirs — it had nothing to do with geography — and they hadn’t expected it. Robert Crofts was also very beautiful. His body was strong and well-muscled, he was slim and upright and his movements were finely coordinated. His rather Germanic features were slightly elongated and his lips were full and red. In the expression of his eyes, which were a deep and luminous brown, there seemed to be an observation on his surroundings that he could not be brought to utter.

The rigors of surviving frontier life may be enough to cause a couple to bury their differences and unhappiness — the introduction of a third party (two’s company, three’s a crowd) brings those feelings poisonously bubbling to the surface.

The ages of the three are important to author Miller’s structure. At fifty-six, Ward is old enough to be Ida’s father. At thirty-three, she is closer in age to Robert than to her husband. And at 18, Robert is a daily reminder to Ida of her own self when she arrived at the station.

In the early chapters of the novel, this plays out as a desperate attempt to define new roles. Ward dislikes Robert from the start. Instead of admiring his capacity for work, he reviles it — perhaps a reflection of his own guilt for laziness and forever starting projects that he never finishes. His response is to make even more unreasonable demands in an attempt to break the young man.

Robert, for his part, discovers that any attempt to escape into a new routine is constantly denied by the owner’s irrational demands. Fifteen-year-old Janet develops a bit of a crush for him, which complicates matters for a youth who is trying to act older than his own years. Life at the station for Robert is based on shifting sand rather than a firm foundation — indeed, an incident featuring a literal sinkhole brings the tension between himself and Ward to a head.

And Ida, who ended up chained to the station by choosing marriage as the path of least resistance, watches all this with growing frustration. As matters get worse, she more and more sees how Robert’s difficulties as a reflection of her own when she arrived there at the same age — all of which re-awakens the dreams and hopes she had for her life fifteen years back.

Incomplete misfits may be able to get by in normal times — the introduction of change tends to make their flaws even more predominant. Once he has established the limitations of the three, Miller carefully shows how grasping at straws to seek a resolution makes things even worse. (Vanderhaeghe, Williams and Stegner all explore this same phenomenon of hopelessness — I’d say it is another constant of frontier fiction. There is a reason why misfits have sought refuge in the un-ordered world.)

Like Williams and Stegner, who have not been getting the attention they deserve, Alex Miller is not a familiar name to Northern Hemisphere audiences. Autumnn Laing attracted positive attention, so hopefully that will soon change. Publishers Allen & Unwin (who kindly provided my review copy) have begun re-issuing his earlier novels — those with a taste for well-written fiction set in the developing North American frontier would be well advised to add this Aussie to their reading lists. He is a wordsmith of substantial talent and while his stories may be set on the other side of the world they have much to say to North American audiences.

December 9, 2013 at 2:59 pm |

Having finished reading Olivia Manning’s Balkan Trilogy on Friday I was somewhat at a loss for what to read next, when I spotted you had a review forthcoming of this novel, Kevin, so I decided to give it a read, it being one of the Alex Miller novels I hadn’t yet got to. And I’m so glad I did – I thought it was wonderful, and your review of it is great. I like how you’ve picked up on the frontier aspect of it, which was something I hadn’t considered.

I’m not sure what blog etiquette is about these things, but I popped my own review of it up on Goodreads this morning so it’s probably easier to provide a link than to repeat myself:

http://www.goodreads.com/review/show/508952362 (hope that works!)

LikeLike

December 9, 2013 at 3:08 pm |

The link works just fine — and many thanks for it. I had thought about trying to include the sexuality that Miller threads throughout the novel, but abandoned the idea because it would simply have taken too many words. So I’ll point visitors here to your review as one which addresses a theme that I fully agree is present throughout the novel that is not addressed in my review.

Personally, having only read two of Miller’s novels (his first and his most recent), I also appreciate your references to what this novel foretells about his later works — I will get to them eventually.

And we are in full agreement that Miller is an author who deserves more readers. I did not find anything in this novel which suggested it had “first novel” flaws — I look forward to later novels getting even better.

LikeLike

December 10, 2013 at 7:58 am |

It sounds rather good. The situation actually sounds like a classic noir setup, though used here obviously in a different way since it’s not a crime novel.

LikeLike

December 10, 2013 at 8:26 am |

I don’t know enough about noir to comment. What I did appreciate was the way that Miller sometimes managed to develop sympathy for the characters (they are all lost souls in some way) while at other times had me gnashing my teeth with how foolish (or just plain mean) they were being.

LikeLike

December 10, 2013 at 8:32 am |

It doesn’t sound like it remotely is noir. That trio though of the older husband, the unhappy and frustrated wife and the young and good-looking newcomer is a classic crime setup. It’s that though because it’s such an innately dramatic setup (it’s also for example used in Polanski’s first film, Knife in the Water). It’s a situation which drives drama, what’s interesting is what the author then uses it to explore.

Williams and Stegner comparisons are interesting too. Your quotes here are good ones but I notice they focus on the characters, how is he on descriptions of the environment?

LikeLike

December 10, 2013 at 8:41 am |

I should have mentioned his treatment of the environment because it is an important constant in the book — sometimes threatening, sometimes welcoming. I found the descriptions very good (particularly since many of them involved a nature that I do not know at all first hand). And Miller also uses it in a different way for each of the characters: for Ida it represents the hopeful aspects of her memory (that’s where the mountain in the title comes in); for Rankin it is a constant “foe” that he has trouble coping with and for Robert it is an entirely new experience, quite unlike the council flats where he grew up.

LikeLike

December 10, 2013 at 8:59 am |

Under 300 pages I see from Amazon. I’ve taken a note of this one. Do you plan to read Evie Wyld’s All the Birds, Singing? I reviewed it recently at mine and it might interest you it strikes me.

LikeLike

December 10, 2013 at 9:18 am |

I did make a note of Wyld’s book when you reviewed it. And then I looked at the staggering pile beside my reading chair. I hope to get to it eventually.

LikeLike

December 10, 2013 at 9:20 am |

That’s what I just did with this one funnily enough. It’s noted, but I have quite a lot presently to be getting on with…

LikeLike

December 10, 2013 at 8:22 am |

There’s also a Canada/Australia/American Great Plains nexus….

LikeLike

December 10, 2013 at 8:27 am |

Quite right — that is why I included Williams and Stegner in my opening comparisons.

LikeLike

December 10, 2013 at 2:05 pm |

I was surprised to read your review of this novel. Being an Aussie I thought I knew all of Miller’s novels, but I’d never heard of this one. You’ve brought this very little known work into the fresh air.

It’s interesting that Miller’s latest (and perhaps his last) novel, Coal Creek, has returned once again to the ‘the bush’, to the ‘outback’, where Miller spent his formative years as a jackeroo when he first arrived here in Australia. Several of his novels are set in harsh rural landscapes – Journey to the Stone Country and Landscape of Farewell – but his work has considerable variety and I greatly enjoyed ‘Conditions of Faith’ and ‘Lovesong’. Hope you enjoy them all.

LikeLike

December 10, 2013 at 2:13 pm |

Thanks for that data — and I will keep an eye out to see if Coal Creek shows up with a North American edition as Autumn Laing did. Certainly, having read only two novels, I already have some appreciation for his versatility.

LikeLike

December 10, 2013 at 3:17 pm |

Glad to see your review of this one, Kevin, although I haven’t read the book myself — and it’s the only one of his that I don’t have in my TBR. I must see if I can order a copy. I’ve been championing him for awhile now and think it’s a travesty he’s not known by audiences outside of Australia. Your review will help spread the word.

Coal Creek is due for release in the UK in March (I think?), so I expect a North American release will follow shortly after. It’s already available on Kindle but I’m holding out for the print edition.

LikeLike

December 10, 2013 at 3:21 pm |

Since my plan is to read his novels in order, I can certainly wait for a few months. Allen & Unwin were kind enough to send me four volumes (thanks to your recommendation) so I have enough on hand to keep me busy for a while.

LikeLike

December 14, 2013 at 7:22 pm |

HI Kevin, I have this one on my TBR, but also the new Coal Creek which has been getting rave reviews here, and a reissue of The Tivington Knot which Kim reviewed a little while ago – I’d never heard of it till then.

So I have an embarrassment of riches to choose from when the summer holidays give me a bit more time to read.

BTW There’s a very moving account of Alex Miller’s boyhood days in Australia in the introduction that he wrote for the Folio Society’s new edition of Tim Winton’s Cloudstreet: Miller came here alone as a 16 year old, and found himself made welcome and accepted simply for what he was by the Aussies he worked amongst, very similar to the people that Winton depicts in his novel. I’m expecting to see that show up in Miller’s novel…

LikeLike

December 14, 2013 at 8:09 pm |

The Tivington Nott is next up on my Miller reading list.

I had read about his own experience working in the Outback as a youth after arriving in Australia — you can tell from this novel that he knows the work very well.

LikeLike