Beautiful Cabbagetown is a very charming ‘village’ in downtown Toronto and has the highest concentration of Victorian homes in North America! Cabbagetown is an engaging part of town and it is a wonderful oasis for the Torontonians lucky enough to live there. Their homes, ‘cottages’, semis and detached Victorians have almost all been lovingly restored. And these cherished homes are the centrepiece of the lives of many interesting professional singles, couples and vibrant young families.

The row houses sell for about $750,000, the “cottages” over $1 million and you don’t want to know what the Victorian “mansions” cost. How times have changed.

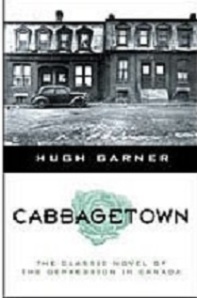

Garner’s Cabbagetown is the same physical neighborhood. The 1968 volume that I read features chapter break “maps” that define its boundaries, Queen Street on the south, Parliament on the west, Gerrard on the north and the Don River on the east — about two square miles that has been a part of Toronto since the mid-1800s. Originally settled by the Irish, it was an arriving-immigrant neighborhood for more than a century — the gentrification process only started about 35 years ago.

(EDIT: Thanks to a comment from Bruce, I have to admit the above para is in error. The Cabbagetown of today is on the north and west edges of the neighborhood described in this book — the community that Garner is writing about has simply disappeared from the map. I would argue that makes the novel even more poignant.)

In spirit, however, Garner’s Cabbagetown is light years removed from the posh contemporary “village”. The novel originally appeared in 1950 in far different form as a “cheap pocketbook” (that’s the author’s description). It was reissued, uncut and unexpurgated, in 1968 — the edition I read — and introduced with a passionate preface from the author:

Toronto’s Cabbagetown remains only a memory to those of us who lived in it when it was a slum. Less than half a mile long and even narrower from north to south, it was situated in the east-central part of the city […].

This continent’s slums have been the living quarters of many immigrant and ethnic poor: Negro, Mexican, Jew, Indian, Italian, Irish, Central European and Puerto Rican. The French Canadians have their Saint-Henri in Montreal and Saint-Saveur in Quebec. Cabbagetown, before 1940, was the home of the social majority, white Protestant English and Scots. It was a sociological phenomenon, the largest Anglo-Saxon slum in North America.

That political agenda is underlined by the time frame of the novel. Book One (“Genesis”) opens in March 1929, coincident with the Wall Street crash. Book Two (“Transition”) is confined to June 1932 to October 1933; Book Three (“Exodus”) extends from the 1933 to 1937 — the depth of the Great Depression.

And having set expectations up for a Canadian version of the (excellent) leftish polemics of Sinclair Lewis or John Steinbeck, let me say that, in its first two sections, Cabbagetown is anything but. Hugh Garner may be angry about what happened to Cabbagetown, but he is determined to paint a picture of a community where struggling individuals find strength in relating to each other and through that build a vision of hope for the future.

Ken Tilling is the first and foremost of these. We meet him on his sixteenth birthday as his school principal says goodbye because Ken is heading into the working world:

He was bitter at his after-school delivery job keeping him from sports and dramatics, and of having to refuse party invitations because of his shabby clothes. He had remained an outsider from the cliques revolving around athletics, the school magazine, the auditorium stage, the possession of a Model T Ford —

But now all this was past. Tomorrow he would get a job, and the money he earned would give him equality with those among whom he had not been equal before. Getting a job was an easy step in the early months of 1929. Business and employment were climbing to unprecedented heights. Columns of help-wanted ads beckoned to anyone able and willing to work. The store windows were full of the retail manifestations of prosperity: bright yellow square-toed shoes to be worn at Easter, new gray suits, the cumbersome polished shells containing the new wonders of radio. Everywhere were new clothes, iceless refrigerators, Rudy Vallee records, banjo ukuleles, bridge lamps, imported English prams, home-brewing supplies, the new Model A Ford, Amos ‘n Andy’s pictures, sporty looking Chevrolets.

When you have grown up in a slum, with an alcoholic single mother, that checklist is a version of what the dream of the future looks like. Ken Tilling, a decent, law-abiding Cabbagetown boy, is determined to pursue it.

There are, of course, other ways out of the slum and Garner is scrupulous in developing them. Crime is one option — Ken does get involved with some friends who choose this path to escape. Aligning yourself with the powerful is another — Ken’s neighbor, Theodore East, opts for this route and casts his fate with the anti-Semitic, fascist forces that were part of Canada’s 1930s. The girls of Cabbagetown have less choice — marrying up is a possibility, but a slim one; trading sexual favors has a quicker return. Ken’s infatuation with Myrla, who makes that latter choice, is a story thread that runs throughout the novel.

What most impressed this reader on my latest reread was the way that Garner kept his anger in check throughout Books One and Two of the novel. Every one of the characters is searching for a better future — and they are dependent on the “safety net” of Cabbagetown, the community, to help them. And I have mentioned only a few — the novel features many, many more from a number of generations.

Alas, this is the 1930s, the post-crash era of the Great Depression, and Garner refuses to sugar coat reality. Ken has to take to riding the rails and 20-cent-a-day forced labor camps. Myrla’s easy choices produce predictable results. Crime doesn’t work and ends in violent death. Book Three (“Exodus”) is relentless, harsh realism without succour — the barriers to escaping Cabbagetown are simply too high for even the nicest of people to scale.

In many ways, I found this revisit of Cabbagetown resulted in two very different novels. The first two Books develop and portray a neighborhood and community of great strength, individuals fighting against the odds and leaning on each other. Whatever route the individual has chosen to get out of Cabbagetown, we want them to succeed. And then, in the final section, Garner delivers the harsh reality: as much as we would like a happy ending, the take-no-prisoners world of capitalist economics refuses to allow it.

We live in a much more complicated economic world now, so parts of Cabbagetown do have a dated feel. Having said that, the forces that are at the root of Garner’s story — both positive and negative — are still very much in play. Cabbagetown, the neighborhood, may have gentrified, but the support that Garner found there is still very much present. In developing the stories of Ken, Myrla and their neighbors, Garner has put a face to the individuals who have to play that game — it may be 70 years since he wrote the first version, but the rules are still the same.

I think it is fair to say that Cabbagetown has fallen off the table of Canadian “must reads” — it deserves more attention. I certainly found this reread rewarding.

September 2, 2013 at 12:54 pm |

never heard of the place or the book before. I checked Amazon and there were a couple of positive reviews so the book seemed to make a positive impact on a few people.

LikeLike

September 2, 2013 at 1:50 pm |

Given your noir interests, Guy, I think this novel has some appeal to you. It has the gritty side, but at least in the first two parts that is offset by a softer set of observations. The final third is right up your alley — at first, I found it somewhat depressing but had to admit that Garner was simply finishing his stories the way that the world of the day would.

LikeLike

September 2, 2013 at 2:00 pm |

A correction: the Cabbagetown of Hugh Garner’s novel is not the same area as what is called Cabbagetown today. Garner’s Cabbagetown was largely bulldozed to make way for the Regent Park housing project in the 1950s (and is in the midst of being remade once again.) What is today called Cabbagetown sits north of Gerrard St and straddles Parliament. The north barrier is the St. James Cemetery. Garner’s sequel, a pretty lousy piece called The Intruders, takes place in the new Cabbagetown, also called Don Vale.

LikeLike

September 2, 2013 at 2:11 pm |

Point taken. If I had extended the quote from Garner, it concludes by describing the bulldozing of the neighborhood and construction of Regent Park (which is about as much of a slum as one could ask for, but I digress). And the map of the realtor whom I quote in opening the review shows a Cabbagetown exactly as you describe — Garner’s Cabbagetown is southeast of the modern version.

All that aside, I still think the comparison holds. Even more poignant, perhaps, is that the Cabbagetown defined by the “maps” in the volume that I read (and the subject of the novel) simply does not exist at all any more.

I was not very impressed with The Intruders either.

(I have put a clarifying paragraph acknowledging my error in the review. Many thanks for updating my lack of Toronto knowledge.)

LikeLike

September 9, 2013 at 5:51 pm |

Hi Kevin; Thanks for the mention. I too enjoyed Hugh Garner’s book Cabbagetown. And I have to say that even though Cabbagetown is expensive now, the character of most of the people who live here is that of helping your neighbours, sharing your stories, being involved in the community. We’re a liberal leaning bunch and many of us are/were writers, artists, actors, film makers etc. I worked in publishing for years and paint part time, my aunt who has lived here for 50 years is a former film maker/artist.

Susanne

http://www.suannehudson.com for more info on Cabbagetown.

LikeLike

September 10, 2013 at 7:47 am |

Thanks for the comment — I was delighted when I found your description on line. I have an outsider’s bit of knowledge about the area (I stayed there with a friend briefly in the 1960s) but it is very limited — as is obvious from Bruce’s comment pointing out that the boundaries of the neighborhood have changed.

LikeLike

September 10, 2013 at 11:07 am |

I have one of those “cheap pocketbook” editions on my stacks, but I haven’t gotten acquainted with its pages yet. I wholly enjoyed Rabindranath Maharaj’s view of Regent Park and Cabbagetown in The Amazing Absorbing Boy, which explores the area from a newcomer’s perspective; it got me out and exploring with a camera for a full day two autumns ago, and I loved every minute in the neighbourhood.

LikeLike

September 10, 2013 at 11:11 am |

Since you are in to “Toronto neighborhood” books, have you read Cary Fagan’s new one (A Bird’s Eye) which I gather is located in the Kensington Market area? It has appeal (I liked his short story collection last year) since I know a little bit about that area as well — but I’ll admit I have held off ordering it until I see what the Giller longlist is. If it doesn’t make that list, I think I’ll mark it down for post-Giller reading.

LikeLike

September 11, 2013 at 12:53 pm |

This sounds excellent, and I’m glad I read the review (I was away when you posted it so almost missed it).

The combination of a non-judgemental opening and then a closing showing how the various hopes fare in the face of economic reality sounds punchy, and much more so than the more usual polemical approach one might expect.

I liked the second quote too. Top stuff.

LikeLike

September 11, 2013 at 1:21 pm |

Given your own youth, I think you would find this interesting. Yes, it is set many years ago, but there are many neighborhoods like Cabbagetown today — although there is no doubt that the ethnic mix is much different.

And what impressed me most (and that I did not remember from my previous readings) was how harshly realistic Garner was in portraying the outcomes in the latter part of the book.

LikeLike

September 17, 2013 at 7:23 am |

Looks like it will be an abebooks job for me Kevin. Seriously out of print, if it ever was in print in the UK.

LikeLike

September 17, 2013 at 7:53 am |

Canadian online stores have a version, but their international shipping costs tend to be prohibitive. Perhaps putting it on a mental holding shelf until you have a three or four book Canadian order — that brings the shipping into line.

LikeLike

September 17, 2013 at 7:56 am |

I’ve popped it in an abebooks basket to pick up at some point. Abebooks has tons of cheap copies happily.

LikeLike