Translated by David Colmer

I don’t often open a review with an excerpt, particularly as long as the one above. I give away no personal secrets in acknowledging that I resort to it only under two sets of circumstances. One is that the excerpt is so powerful in capturing the novel that it demands prominence — that obviously is not the case here. The other, alas more frequent, is that I can't find the words to adequately capture the strengths and/or weaknesses of an author's approach — the best option seems to be to supply a sample, briefly describe my reaction and let visitors here decide for themselves.Of the ten white geese in the field next to the drive, only seven were left a couple of weeks later. All she found of the other three were feathers and one orange foot. The remaining birds stood by impassively and ate the grass. She couldn’t think of any predator other than a fox, but she wouldn’t have been surprised to hear that there were wolves or even bears in the area. She felt that she was to blame for the geese being eaten, that she was responsible for their survival.

‘Drive’ was a flattering word for the winding dirt track, about a kilometre and half long and patched here and there with a load of crushed brick or broken roof tiles. The land along the drive — meadows, bog, woods — belonged to the house, mainly because it was hilly. The goose field, at least, was fenced neatly with barbed wire. It didn’t save them. Once, someone had dug them three ponds, each a little lower than the last and all three fed by the same invisible spring. Once, a wooden hut had stood next to those ponds: now it was little more than a capsized roof with a sagging bench in front of it.

For this reader, those two paragraphs do concisely illustrate both the narrative and descriptive threads that are the warp and woof of Gerbrand Bakker's The Detour. “Narrative?”, you might well ask in puzzlement — be forewarned that the example of the disappearing geese is a fair representation of “action” as it takes place in the novel. Description, on the other hand, is frequently present — comprehensive, yet concisely rendered, but often piling observation on top of observation in a manner that leaves the reader’s head swimming.

The excerpt comes from early in the book. At this point, we know that a Dutch woman, Emilie, is experiencing her first few days at a rural house she has rented in Wales. She has already found a stone circle with a colony of badgers: “When they noticed her they ambled off into the flowering gorse.” An extensive description of the interior of the house and its exterior surroundings (stream, gardens, trails, nearby villages) soon follows. Again, it is fair to say that Bakker wants his readers to have a firm understand of “where” before he gets to “what”, let only “why”, in his story.

I admit the following somewhat spoils his deliberate approach, but in the next few chapters (they are very short — 60 in a 230-page book) he offers some murky hints on what has caused Emilie to relocate to Wales, a decision that clearly represents getting away from something rather than heading towards some bright new future:

Emilie did not let her husband know she was leaving. There are occasional chapters which return to Amsterdam and feature him: Bakker uses his confusion and eventual search for her as a way of revisiting elements of that back story.

Most of the story, however, is concentrated on what she discovers and does at her new “home” in Wales, near Mount Snowden. Given Bakker’s tilt to description, most of that discovery involves the natural elements, but two significant Welsh characters do get introduced. Rhys Jones is a sheep farmer who rents grazing land owned by the deceased widower whose house Emilie has rented. More important is Bradwen, a 20-year-old student mapping a long-distance trekking path who shows up one day. His overnight stay gets extended and he soon becomes not just Emilie’s helpmate in cleaning up the property but her contact with the external world — not just this new one but, metaphorically at least, also the one that she is fleeing.

That’s pretty much all there is to The Detour — as you may have concluded, the title is quite apt. Okay, there is eventually a sort of resolution, but even that when it happens seems to be more a part of the continuum of the story than an actual conclusion.

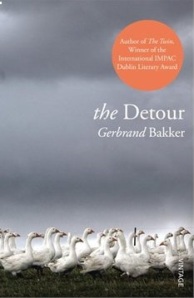

Gerbrand Bakker is one of those translated authors who has won significant attention in the English-language publishing world. His previous novel, The Twin, won the 2010 IMPAC Award — if you don’t know his work, I’d urge you to check that review as well because in tone and structure that volume has many similarities with this one. The Detour, meanwhile, won this year’s Independent Foreign Fiction Prize. While I appreciated them both, I would be the first to admit that Bakker is one of those writers who is an acquired taste.

There is not a lot of humor in The Detour (although there are occasional bits), but I can’t resist concluding this review with some. One of the bloggers you will find on my blogroll is anokatony at Tony’s Book World who was inspired in his review of The Detour a few weeks back to create the genre of “Gorse Novel” (you’ll note from a quote in this review that a reference to “gorse” appears early, and reappears not infrequently, in this novel):

Here are the characteristics of a Gorse Novel.

1. A Gorse Novel takes place in an isolated rural area where the people are few and far between. But these lonely souls make up for their sparseness with all of their Eccentricities.

2. These folks in a Gorse Novel are necessarily very close to nature, and the novel will contain elaborate descriptions of the birds, the other wildlife, the plants, or the weather that will usually put all but the most dedicated readers to restful sleep.

3. People in a Gorse Novel don’t say much, and when they do, it is only in a few short words which are supposed to be Greatly Significant. So when a character says “Storm’s a coming”, it means much more than that a storm is approaching.

4. Nothing much happens in a Gorse Novel. There is an eerie sense of quiet and calm, so finally when some tiny event happens like an itch or a cough, it seems as momentous as an earthquake.

I liked The Detour (which is called Ten White Geese in U.S. editions, incidentally) more than Tony did, but I can’t dispute that it fits all four of those characteristics. And I did want to introduce the concept of Gorse Novel to regular visitors here. Many of you may recall that another blogging friend (John Self at Asylum) a few year’s back invented the description of Widescreen Novel: “…ambitious works containing a large cast of characters, far flung geographical settings, and modern history or political issues rendered in fiction.” (You can find an interesting discussion of the Widescreen Novel in my review and the ensuing comments of Kamila Shamsie’s Burnt Shadows.) I’d say John and Tony have succeeded in creating apt descriptions of two poles of contemporary fiction. The Detour is pretty much as Gorse a novel as you can get — maybe the real reason that I opened with that excerpt is that it includes so many of Tony’s characteristics. 🙂

July 10, 2013 at 1:37 pm |

When hiking through gorse, there are 2 recurring sentiments:

” gosh this stuff is all the same, and goes on and on” and

” my legs are itchy”

Sounds like versions of these themes come through in this book.

LikeLike

July 10, 2013 at 1:39 pm |

They do. But then again, sometimes you have to experience the gorse (and the itchy legs) to get access to all that surrounds it.

LikeLike

July 10, 2013 at 1:42 pm |

Yes, of course. Looking at the wider canvas, as we say…..

LikeLike

July 10, 2013 at 1:56 pm |

Thank you for the concept of the Gorse Novel – a useful category.

I agree that there are similarities in style and tone between The Detour and the Twin, but comparing the two I think The Twin is positively action packed. In Detour nothing of any significance ever seemed to happen and the character’s actions/decisions were mystifying. In The Twin we have a complex family history involving betrayals and passion, the deep bond of twins, the return of an old love, and the narrator finally casts the problems of the past aside and assumes control of his own life.

I can imagine The Twin as a film ( mind you the audience might be limited) – it’s even got a ‘happy’ ending, but The Detour couldn’t be a film because it hasn’t got any plot, structure or development. Some writers improve with time but it seems to me that Bakker has gone the other way.

But I must declare a bias. I’m a donkey tragic and The Twin gets a big tick from me for the significant role given to these wonderful creatures. Ransom by David Malouf also scores well in this dimension.

LikeLike

July 10, 2013 at 2:01 pm |

I would pick The Twin over this one as well, for exactly the reasons that you mention. Having said that, this is quite a good character study of an individual who suffers from quite substantial gaps — a study in introspection of the incomplete, if you will.

LikeLike

July 10, 2013 at 2:57 pm |

Thanks so much for introducing me to the concept of “gorse novel”. Made me laugh out loud. Perhaps I could even like a gorse novel, but I didn’t like this one. The protagonist here seems so very artificial whereas the twin was a real person trying to come to terms with his difficult past.

LikeLike

July 10, 2013 at 3:04 pm |

Well, Tony deserves the credit for the concept — but I will take secondary honors for passing it on. One thing that is conspicuously lacking from a gorse novel is any emotional attachment for the reader. That was certainly present in The Twin and, for me at least, simply did not occur here: Emilie’s challenges, both past and present, read more like an inventory than anything else. Despite that, I was interested in the way that Bakker portrayed her response (which pretty much always comes down to evasion) since I think it is a fairly common one, although not often found in fiction.

LikeLike

July 10, 2013 at 6:05 pm |

I really enjoy reading it but I have to speed read through the book and then savour it chapter by chapter on a rainy day. If I read it at the ‘usual’ speed, I would get bogged down by all the details and I usually forget what it was about (the plot)

LikeLike

July 10, 2013 at 7:45 pm |

I guess that is one approach. I read quite quickly and I will admit that one of my problems with books (like this one) that feature a lot of description is that I have to force myself to slow down while I build a mental picture of the scene. Particularly when there is so little plot to serve as a grounding point, it means I spend a fair bit of time floundering around.

LikeLike

July 10, 2013 at 7:42 pm |

Kevin, thanks for the mention. I never realized that the concept of a Gorse Novel would catch on to this extent. I never hiked through gorse, but will take Sheila’s word for it.

LikeLike

July 10, 2013 at 7:51 pm |

The label made sense to me the moment I read it, not just for this book but some others that come to mind. And I think you can see from the comments that it has had the same effect on a number of others.

LikeLike

July 12, 2013 at 1:27 pm |

Even though the idea of a Gorse Novel (and its subsequent definition) seems to arise from a frustration or impatience with the book, this one sounds as though I’d like it–as long as there’s not too many other geese body parts.

LikeLike

July 12, 2013 at 1:29 pm |

The reference to the foot that I quoted is the only goose body part that appears.

LikeLike

July 12, 2013 at 5:30 pm |

good to know. Don’t want some mad gorse murderer running around loose.

LikeLike

July 16, 2013 at 5:51 am |

Fans of Patrick Hamilton’s Gorse Trilogy are now well and truly confused….

LikeLike

July 16, 2013 at 7:33 am |

I’ll be they are. Then again, they are a kind of Urban Gorse.

LikeLike

July 16, 2013 at 7:09 am |

I’m actually rather tempted by this, but then the prospect of rural isolation has long appealed to me (and long shall, provided I never actually experience it).

Thanks for passing on the gorse novel idea, it is brilliant. I still use widescreen novel, though since I dislike them I don’t use it that much as I tend not to read them. Not sure I’ll become a gorse novel afficionado either, the landscape can only bear so much meaning. Sometimes a storm should just be a storm. Not every rifle needs to be fired in the third act.

LikeLike

July 16, 2013 at 7:40 am |

Gorse novels are not necessarily bad — it’s just that the author sets the bar arbitrarily high in accepting the limitations that are involved. I’d say Hardy is a good early example (then again, maybe the frustrations of the challenges were why he turned to poetry 🙂 ).

As you can see from the tilt of the comments, I’d recommend The Twin if you have not yet read any Bakker. I was reminded of it a number of times when I was reading Satantango and I know how much you liked that novel.

LikeLike