Translated by Mark Polizzotti

Translated by Mark Polizzotti

One of my shortcomings as a reader gets exposed almost every time I first encounter — and like — an established writer whose work I don’t know. On the “patient-excited” continuum, you can place me firmly at the “excited” end. Even when the logical, thinking part of me says waiting a month or two before reading another book would be advisable, I can’t wait to order the backlist and dive right in.

So it was with Jean Echenoz. As regular visitors to this blog will know, I was very impressed with Ravel, his IMPAC short-listed fictional biography of the French composer. Hence, two of his previous works — Piano and I’m Gone were on the way almost as soon as the Ravel cover was closed.

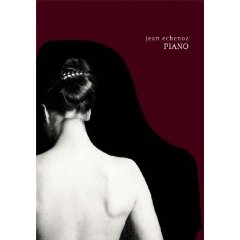

While I’m Gone was a Prix Goncourt winner, the entrancing cover of Piano moved it immediately to the top of the pile. (Judging books by their cover is another short-coming but we’ll save that for a later post). I do have to say that The New Press which published both Ravel and Piano deserves high praise for the covers of both books — these slim, well-produced hardcovers are as physically attractive books as any I have read in a long time.

I knew from some internet scanning that Ravel was not typical of Echenoz’s work. Grounded in the composer’s life, it did not have the surreal — often bizarre — twists of plot that characterize his previous novels. Piano has that in spades.

The book’s central character is Max Delmarc, a 50-year-old concert pianist whom we meet as part of a strolling pair on the streets of Paris:

One, slightly taller than average says nothing. Under a large, light-colored raincoat buttoned to the neck, he is wearing a black suit with a black bow tie. Small cufflinks with onyx-quartz mounts punctuate his immaculate wrists. He is, in short, very well dressed, though his pallid face and gaping eyes suggest a worried frame of mind. His white hair is brushed back. He is afraid. He is going to die a violent death in twenty-two days but, as he is yet unaware of this, that is not what he is afraid of.

Announcing that your central character will die in precisely twenty-two days in paragraph two of a book is not really conventional — Echenoz is definitely not conventional. And since that is not the reason for his fear, what is? We soon find that the second figure explains that. Accomplished a pianist as he is, Max is terrified of performing — and responds to that terror with alcohol. The other half of the walking pair is Bernie, a young man retained by Max’s imressario to keep him off the pre-concert sauce and, literally, push him onto stage and at the piano at the appropriate time.

A few bars into the piece (Chopin’s Piano Concerto #2, which Max knows so well that he is bored with it at this point) and all is well. Plus the deal with the impressario is that he gets to imbibe after the concert. While we soon discover that, along with drink, Max likes to look at and build scenarios around beautiful women, it is the music that dominates his life. Here’s the description of the taping of a concert that will be televised:

After disembodied voices had given the countdown, the concert could begin. The conductor was fairly exasperating, full of mannered grimances, unctuous and enveloping motions, coded little signs addressed to different categories of performers, fingers on his lips and inopportune thrusts of his hips. Following his lead, the instrumentalists themselves began to act like wise guys: taking advantage of a frill in the score that allowed him to shine a little, to stand out from the masses for the space of a few measures, an oboist demonstrated extreme concentration, even overplaying it to win the right to a close-up. Thanks to several highlighted phrases allocated to them, two English horns also did their little number a moment later. And Max, who had quickly lost the scrap of stage fright that had held him that day and was even starting to feel bored, himself began to make pianist faces in turn, looking preoccupied, pulling his head deep into his shoulders or excessively arching his back, depending on the tempo; smiling at the instrument, the work, the very essence of music, himself — you have to keep interested somehow.

I apologize for the length of that excerpt but it represents all that is Echenoz and his ability to create word pictures of the highest order (and equally high marks to the translator for bringing them into English). On the one hand, the eye for detail and the Proust-like cascade of it that precedes the subject and/or object of the sentence. But also, the metaphor of the performance itself. For just as the musicians use the formal structure of the piece to create their riffs and make their statement, the author uses the structure of the novel mainly as a platform for his own improvisations. The book’s strength is in those “improvisations”, not the plot.

Max does get stabbed and die about one-third of the way through the book and wakes up in the Orientation Center, Echenoz’s version of Purgatory, from which he will be assigned to either the park or the urban zone for the rest of time. Allow me one more Echenoz riff:

White in color and emerging from who knows where, this second figure seemed gently but firmly to admonish Yellow Bathrobe, who immediately vanished. Apparently White Silhouette then noticed Max, who watched it walk toward him, become transformed in its approach into a young woman who was the spitting image of Peggy Lee — tall, nurse’s blouse, very light hair pulled back and held with a hair tie. With the same implacable softness, she enjoined Max to go back into his room.

“You have to stay in here,” she said — moreover in Peggy Lee’s voice. “Someone will be here to see you soon.

“But,” started Max, getting no further, as the young woman immediately negated this incipient objection with a light rustllng of her fingers, deployed like a flight of birds in the air between them. When you get down to it, she did look phenomenally like Peggy Lee, the same kind of big, milk-fed blonde, with a fleshy, wide mouth, and excessive lower lip forming the permanent smile of a zealous camp counselor. More reassuring than arousing, she exuded complete wholesomeness and strict morals.

No marks for guessing that it is, in fact, Peggy Lee. As well, no marks for figuring out whether Max gets assigned to the park or the urban zone — in analysing his meagre volume of sins, he humanely manages to completely overlook the most obvious one.

While I liked Ravel somewhat more than Piano, that says more about me as a reader than it does about either book. I enjoyed and appreciated both books — the grounding in reality of Ravel is probably more to my taste. And I did not do Echenoz any favour by reading Piano so quickly after the first book. The concise and precise digressions, with their incredible detail, are a feature of both books and can be grating, even though they are the best parts of the book. I doubt that I would have noticed that if I had waited a couple of months before reading Piano. Echenoz is for sipping, not gulping.

Which is precisely what I propose to do with the rest of his work. Even I should be able to put a lid on excitement, or at least cork it for a bit.

June 6, 2009 at 7:44 pm |

It’s great to be excited about a writer. Fun review.

I am now hooked on Joseph Boyden and hope to start a newer novel by Jane Urquhart soon (my Canadian addictions!)

But, I must review them. I have been derelict.

LikeLike

June 6, 2009 at 11:04 pm |

How interesting to see the US (or North American anyway) cover for Piano, particularly as it earned your praise, Kevin. The UK cover could not be more different: loose, colourful, cartoonish almost. I admit I picked it up in the bookstore a year or so ago but hadn’t heard of Echenoz at that time. Now that I have, the store no longer has it. I will pick it up eventually – and have only skimmed your review to avoid directing my thoughts in any particular direction before reading the book – but in the meantime, let us praise chance for having prevented me from adding to my teetering piles just this once.

LikeLike

June 6, 2009 at 11:13 pm |

I hadn’t looked at the UK cover until your comment — I sure don’t like it. Then again, you do get a paperback version there so the price is about half that of the one I read (and The New Press doesn’t seem too anxious to put a paperback out). And I just discovered from searching Amazon and Chapters after your comment came in that Piano is now sold out on both sites. I think you will like Echenoz when you get to him, but I can’t see any reason why you should be in a big rush.

LikeLike

June 7, 2009 at 9:50 am |

Oh, I should say that I have got to Echenoz – I read Ravel last month. I liked it very much, but just couldn’t think of what I might say about it in a review. Perhaps I should just do a one-line review, linking to yours. (More likely is that I will reread it – no hardship, or need for much time set aside – and write about it then.)

LikeLike

June 10, 2009 at 12:57 am |

Also do not like the UK cover but really enjoyed your review here. Allow me to cross post on the Lost in Translation reading challenge dedicated page? Many thanks for considering!

LikeLike

June 10, 2009 at 2:58 am |

By all means Frances — thanks for the offer.

LikeLike

December 19, 2013 at 6:35 am |

Absolutely loved this, and didn’t mind the cover…wonderful dexterity from Echenoz when slipping perspectives and registers, and that trickiest of things to pull off: seriousness and mirth. It felt like a Hal Hartley piece minus the one particularly grating minor character.

LikeLike

December 19, 2013 at 8:16 am |

Piano was not only fun to read I can report that almost five years on it stays strong in memory. The first few paragraphs of the book brought the whole experience concretely back to mind.

I haven’t read an Echenoz for some time and know that there is at least one more kicking around here somewhere (a recent pipe disaster has lead to construction confusion and locked-away books for the last few months). I’ll get to it sometime next year.

LikeLike

December 20, 2013 at 3:17 am |

It was such a pleasure to read, I will certainly read more Echenoz.

What is this disaster you speak of? Sounds bad. What’s happened there? I know you said you had around 4.5k books in your basement…

LikeLike

December 20, 2013 at 7:27 am |

A section of the cast iron pipe that carries waste water and sewage from our 100-year-old house (that is ancient by Calgary standards) collapsed resulting in a basement flood (that fortunately did not get up to any of the books). That meant an exterior trench to replace it. Worse however was that the 75-year-old tiles on the floor had asbestos in them, which meant sealing the whole area off and a week-long process to get them and the adhesive out. Followed by retiling. We are now two months in and awaiting completion of the new footings for the bookshelves before they can be restocked. Of course at each step some minor new extra problem involving a few more days work (and usually a new trade) has been found.

And no we are not doing any of this ourselves, but waiting around for tradesmen to arrive is not one of life’s most satisfying activities.

LikeLike