One of the first three books reviewed on this blog was Paris Trance, by Geoff Dyer. While I would love to say that it was careful consideration that produced those first three, it was anything but. It was the first week of January, a pretty boring reading time most years. In addition to Paris Trance, I’d just finished reading Patrick McCabe’s The Holy City and Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth. And finally I was feeling guilty that I was clogging up the comments section of other people’s blogs with thoughts of increasing length, too lazy to maintain a blog of my own.

One of the first three books reviewed on this blog was Paris Trance, by Geoff Dyer. While I would love to say that it was careful consideration that produced those first three, it was anything but. It was the first week of January, a pretty boring reading time most years. In addition to Paris Trance, I’d just finished reading Patrick McCabe’s The Holy City and Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth. And finally I was feeling guilty that I was clogging up the comments section of other people’s blogs with thoughts of increasing length, too lazy to maintain a blog of my own.

So on the afternoon of January 7, I signed on to wordpress.com, registered KevinfromCanada and wrote a quick review of The Holy City. I thought I’d sleep on it, check the review in the morning and then, if I decided to proceed, draft reviews of the other two (and maybe a few others) and then launch the blog. Rookie that I was, I didn’t even realize that I had inadvertently linked to a few other blogs — and when I got up the next morning to check my draft review, I was greeted by two comments from fellow bloggers welcoming me to the blogging world. Like it or not, I had two reviews to produce that day to get up to speed.

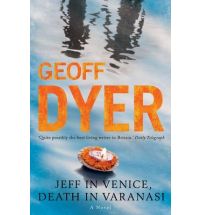

Talk about a “soft launch” — KevinfromCanada was launched without the creator even deciding he was going to do it. I have loved every moment since and, like many a proud entrepreneur, couldn’t stand the idea of waiting for a full year before celebrating a blog birthday. So, when I discovered the Geoff Dyer’s Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi was due for release in Canada on April 7, the end of the First Quarter for the enterprise KevinfromCanada, I resolved that it would be the subject of the first quarter report. Dyer was my favorite of those first three books and I have read many good books in the last three months — but I am delighted with this choice as the “first quarter report” . This marvelous book definitely stands in the front rank of all those good books.

One of those welcoming messages was from John Self at Asylum (one of the blogs I had been clogging up). It was also John who had introduced me to Dyer with a review of The Missing of the Somme (that review along with John’s thoughts on this book can be found here). John’s recent review also pointed me to an excellent Guardian interview with Dyer — the quotes and observations from the author that appear here come from that interview.

As its title suggests, Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi comes in two parts. Dyer comments:

With my usual unerring eye for commercial suicide…I originally wanted to entitle the book ‘A Diptych’ to make clear the two stories were separate. But I was urged not to, and when I saw a mock-up of the front cover with the word ‘diptych’ on it, I thought ‘Oh God, that’s too pretentious even for me’. So I agreed to knock it off. But I’m beginning now to wonder if I shouldn’t have let it stand.

Okay, we’ll take the author at his word — we are dealing with two stories. But the nature of a diptych (as opposed to a book of two novellas) is that some sort of relation between the two is implied.

The central character of Jeff in Venice is Jeff Atman, a London-based freelance journalist who has an assignment from Kulchur magazine to produce a “colour” piece on the 2003 Venice Biennale. Jeff and the world do not get along very well — he would quit his job, except as a freelance journalist he pretty much has already done that. He also has an issue with what he calls “muted karaoke”:

A woman pushing an all-terrain pram glanced quickly at him and looked away even more quickly. He must have been doing that thing, not talking aloud to himself, but forming words with his mouth, unconsciously lip-synching the torrent of grievances that tumbled constantly through his head. He held his mouth firmly shut. He had to stop doing that. Of all the things he had to stop doing or start doing, that was right at the top of the list.

As my wife could tell you, I have exactly that habit when I am upset (fortunately, it seems to be ebbing). One of the great things about Dyer is that these wonderful little observational time bombs keep exploding right there on the page. Consider this description a few pages later of the airline that Jeff is flying from Stansted to Venice:

Ailrines like Ryanair or EasyJet tried to dress up their no-frills status; Meteor basked in theirs. What you saw was what you got. More accurately, what you didn’t get. This was budget flying taken to its limit. They had stripped away everything that made flying slightly more agreeable and what you were left with was the basically disagreeable experience of getting from A to B, even though B turned out not to be in B at all, but in the neighboring city C, or even country D.

Anybody else ever flown Meteor Air? Sure enough, Jeff lands a long, hot and smelly coach ride from Venice.

Art may be the excuse for the Biennale but it is not what it is really about (Jeff’s already invented his line for the Biennale: “But you write mainly about art?” “Not really. I’m not a very visual person.”) . While you do visit the pavilions during the day, it is about the parties and the free food, drink and drugs that are part of those parties. In Jeff’s case (and many others), it is also worrying constantly about the parties to which you don’t have an invitation. Film has Cannes, Sundance and similar festivals — the art world has the Biennale, Basel and some others. The medium may be different, the carnival is pretty much the same.

Also, you want to get laid — maybe even mainly get laid — even if you are a failure (with just-dyed hair) in his mid-forties, like Jeff.

The action part of Jeff in Venice starts at his first party when he meets and falls in Biennale love with Laura Freeman, a curator from a gallery in Los Angeles. It takes a day for them to reconnect (during which Jeff actually visits a number of exhibitions); from then on, this story is about how they experience both Venice and each other. Their conversation, like the art they criticize, is banal. On the other hand, the sense of touch with which they experience each other and Venice is anything but banal. Shortly before his death, John Updike was given a lifetime award for bad sex writing — with this book alone Dyer ensures he will never be awarded that dubious distinction.

Between this creepy veneer of parties, drinks, drugs and sex, however, there is a powerful undercurrent: the art, not just of the Biennale, but of Venice, does matter. In the Norwegian pavilion, Jeff is intrigued by a lengthy wall of circular yellow and black dartboards that are, in fact, dartboards. Viewers are invited to throw darts with red and green flights at the boards — the color and texture of the installation obviously changes as the day goes on. (Like quite a bit of Dyer, this isn’t fiction — it is a real installation from the 2007 Biennale, interesting pictures of which can be found here.) He also quite likes an installation (oh for the days when we could go and look at paintings instead of “experiencing an installation” — but I guess my age is showing) in the Finnish pavilion:

A simple wooden boat was adrift in a frozen sea of broken, multi-coloured Murano glass — discards and fragments, presumably from the factories near Venice. Painted a dull red, the interior of the boat was gradually filling up with water dripping from the ceiling. Every now and again — so infrequently Jeff wondered if he was imagining it — the boat rocked slightly.

Yes, real again from the 2007 Biennale — see it here. Even if you decide not to read the book, do check out those images. As for me, I can’t imagine how frustrating it would be to read Dyer before Google existed.

Those two installations are only part of the art sub-text however. On the way to Venice, Jeff was reading a Mary McCarthy book, Venice Observed, that discusses Giorgione’s The Tempest (here), so he goes to see — and is impressed by — that. And when Laura has left, with the future of their affair-relationship uncertain, he seeks refuge in the Tinteretto’s at the Scuola Grande di San Rocco (images here, but this one is tough because it is hard to convey since they cover all four walls and the ceiling).

Consider for a moment: These two are installations, albeit from more than 400 years ago (I retract that lamentation of a few paragraphs ago). Just as the dartboards and boat created a reason for celebration and festival, they too were produced for celebration, and the occasional festival (there is a reason this post is going up on Good Friday, after all). Jeff’s visit to the Scuola comes in the final pages of Part One — it is a spoiler to say how it ends.

The central character in Death in Varanasi is a mature freelance journalist based in London who has been given a last minute assignment for a travel piece on Varanasi (also known as Benares, the City of Light and a number of things). While the first part was told in the third person, this is a first person narrator and we never know his name. Dyer says in the Guardian interview he may or may not be Jeff Atman — this review will assume he is. It is also not stated whether this story takes place before or after the first. (And I promise there will be no distracting links in this part of the review.)

If sight and touch are the senses of Jeff in Venice, Dyer wastes no time establishing that sound will be a primary sense in this story:

From the airport to the hotel, Sanjay had used the horn excessively; now that we were in the city proper, instead of using it repeatedly, he kept it going all the time. So did everyone else. Unlike everything else, this did make sense. Why take your hand off the horn when, a split-second later, you’d have to put it back on?

Loud sound is a constant feature of this book; Jeff even takes to wearing his iPod, turned high, just to escape it. That doesn’t work. Even the concerts that are a part of this story (sound is the dominant sense) feature the discordant, physical Indian music that certainly raises no thoughts of an adagio.

The secondary sense, but almost as great as that of sound, is smell. The remnants of defecation — animal and human — are everywhere, forming a kind of tar. Vegetable waste adds to the overwhelming odor. Even the marigold garlands thrown around Jeff when he visits the temples (for 50 rupees, please) have a rotting stink. Not to mention that Varanasi is a crematorium site and the funeral pyres are constantly burning.

Unlike the chic Venice of the Biennale, Varanasi is about as horrible an environment as you can get. But where our first character fled when he could, our second can’t leave. He moves into a more central, less grand, hotel — becomes its only long-term guest. As the narrator observes, he does not so much go native as become an older version of the dread-locked trekkers, except that while they flow through, he stays on. Eventually (no real surprise this) he discovers some things about himself.

While the two stories have some superficial similarities, this is obviously a diptych in the literary version of a Francis Bacon triptych where the relationship between the parts is not just obscure, it seems non-existent. It is not a common form — in most two-part books, Part Two flows from Part One. Having said that, I can think of two recent similar examples — Anne Michaels The Winter Vault (my review is here) and Michael Ondaatje’s Divisidero. I think both those authors failed — Part one in each book was interesting, the second half merely baffling. I think Dyer succeeds — why?

I am indebted again to John Self for supplying the clue to my interpretation (and I emphasize that others are certainly possible) with a piece of knowledge from his review I did not have:

When the protagonist’s name – Jeffrey Atman – was disclosed in the opening sentence of Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi, a little something in me died. I recalled from Siddhartha that Atman was a Hindu spiritualist term for the eternal soul, and I dreaded the onset of a new age tale of ‘finding oneself’. But I needn’t have worried: at least, not yet.

I think it is safe to assume that Dyer’s choice was deliberate and, carefully structured and hidden by witticisms as it is, there is an element of soul-searching, if not eternal soul-finding, in the two parts of this diptych. And my interpretation is that the unifying link is the counter-intuitive use of the four senses that Dyer employs in the book (taste is present in both parts, but is used in similar ways).

Sight (as in contemplating art) and touch (as in caress) are normally thought of as creating the kind contemplative peace associated with finding oneself. Sound (as in blaring traffic) and smell (as in rotting shit) would seem to produce the exact opposite. Yet in this book, the first two senses generate a form of contemplation avoidance — the latter nourish introspection. The author leaves it to the reader to figure out why.

Am I over-interpreting? Maybe — I am the kind of reader who likes to start the thinking process anew when I close the cover of a book and this book obviously did that for me. I certainly don’t want to leave the impression that that is the only interpretation — or indeed that any interpretation at all is required. Dyer is a wonderful writer to read (I finished all but the last 20 pages of this book in one read on the day it arrived — and I only stopped there because I wanted to save the ending for the next day). But this is not just a satisfying book, it can be challenging as well — there is a lot of “reader control” in just how far you want to take it, which is the mark of a truly good book.

That is the conclusion of my first quarter report. My thanks to everyone who has visited KevinfromCanada in these first three months and special thanks to those who have taken the time to observe and comment — I hope you will keep on visiting and commenting. And I hope that the thoughts here are at least on the positive side of neutral in terms of enhancing your reading experience. I already know what the theme of the sixth month report will be. And there will be no prize for guessing the subject matter of the nine month report — the ManBooker Prize is announced on October 6, so I’ll be moving that report up one day to salute the jury on their decision to agree with my selection — or, more likely, whine (yet again) about why my choice was ignored. Cheers.

April 10, 2009 at 10:06 am |

An excellent review, Kevin, and I am delighted to be the first to comment on your quarter-anniversary post as I was (I think?) the first to comment on your first post.

Your inclusion of links to the artworks referred to in the book is valuable.

The question now must be where you are going to go from here with Dyer? Am I right in thinking you’ve read two of his novels but none of his non-fiction? If so, then that needs to be corrected pronto – his non-fiction is in my view more interesting than his fiction. I recommend of course The Missing of the Somme, but also Out of Sheer Rage and Yoga for People Who Can’t Be Bothered to Do It (which I think has some similarity with Jeff in Venice). Also his collection of “essays, reviews, misadventures” Anglo-English Attitudes shows the sheer breadth of his interests.

I’ll also use this opportunity to plug the fact that I have an interview with Dyer coming up on my blog later this month. As a teaser, I can exclusively reveal that he called one of my questions “unbelievably flirtatious”.

LikeLike

April 10, 2009 at 2:29 pm |

1. You were the first, so I guess you can claim you were the one who pushed the hesitant typist off the edge.

2. I haven’t started the non-fiction. The Missing of the Somme and Out of Sheer Rage are battling with the collection — suspect I’ll order them all and then choose. Non-fiction will be next.

3. Love the new gravatar picture and please keep changing them as your son grows. Your questions may be “unbelievably flirtatious”, your son is already acquiring some ingenu qualities. (Aside to visitors: Dyer dedicates the book to his wife, Rebecca, so don’t jump to conclusions.)

4. I am pondering why Dyer has a relatively low profile in North America — I think it is because his eclectic non-fiction-fiction-journalism mix doesn’t fit any convenient box, so the trade just ignores him. If you get a chance for follow-up questions in your interview, could you ask (or I will raise it in comments and see if he responds).

5. Finally, John, thank you for getting me into this, in your own way of course. And thanks also for all of the interesting authors to which you have pointed me.

LikeLike

April 10, 2009 at 4:11 pm |

Okay, you and John have convinced me that there is much more to Dyer than bad (or perhaps I’m in the minority there) titles. I’m not sure when I’ll get to him, but he’s on my watch-for-at-all-costs list.

By the way, happy first quarter! I’ve enjoyed it all!

LikeLike

April 10, 2009 at 4:16 pm |

My hypothesis on the titles is that they are a not-very-good way of Dyer trying to say “don’t take me too seriously”. Of course, as his quote indicates, this produces an unerring aptitude for commercial suicide. And I do think he should be taken seriously — although I must admit the jokes and gags along the way certainly are refreshing. I think you will quite enjoy him when you get to him.

LikeLike

April 10, 2009 at 6:32 pm |

There is definitely a large gap between the titles Jeff in Venice and Diptych; one takes itself very seriously and the other . . . not so much. Though I see how both can be considered a yearning for commercial suicide. I’ll see what I can do to make sure his yearning doesn’t succeed because of me!

LikeLike

April 10, 2009 at 9:04 pm |

Just to clarify, Trevor, my impression was that Dyer wanted not to call the book Diptych but to subtitle it thus: Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi: a Diptych. (Yes, it is too pretentious even for him.) Like Kevin, I think you would like his writing, indeed, I can’t think of many who wouldn’t find at least one of his books to appeal to them.

Incidentally Kevin, another very good interview with Dyer is here – it dates from 2003, and the publication of Yoga for People Who Can’t Be Bothered to Do It. he seems to have a real rapport with the interviewer.

Also incidentally, I believe Dyer is travelling to the USA next week to promote the publication of Jeff in Venice there – I don’t know if he will be making it north of the border, but it might be worthwhile keeping an eye out. Here are the events planned so far.

LikeLike

April 10, 2009 at 11:45 pm |

Thanks, John — I’d say it looks like he is making a trip to California, which he said in the Guardian interview that he likes very much. One east coast stop and then off to the West Coast. And I can’t help but note that Dyer is going to Menlo Park — which is where the present-day narrator in Stegner’s Angle of Repose was afraid his son wanted to ship him to the nursing home.

On the “diptych” issue, the Canongate version has “A Novel” in small white type, under the pretty small title, which is dominated by the author’s name — I suspect that’s where “A Diptych” would have gone and it would have looked pretty stupid (in my opinion, of course). I’d also say the Canongate cover writer did a pretty good job of indicating the difference on the inside cover.

I was also interested in Michael Ondaatje’s blurb: “A raucous delight, Jeff in Venice is truly surprising — very funny, full of nerve, gutsy and delicious. Venice will never be the same again.” Given that Ondaatje’s last book was a diptych, one thinks he could have found a way to acknowledge both parts. Then again, I have advised several friends that if they like Part One of Divisidero they should set the book aside and make up their own Part Two, because it would be better than the author’s. I know, I shouldn’t say things like that on the blog but those who have ignored my advice have indicated that they wish they had taken it.

LikeLike

April 11, 2009 at 9:28 pm |

I liked Divisadero, even the whiplash-inducing change of, well, everything in the second part. Partly I just admired Ondaatje’s balls, but I also welcome anything that makes me think I will need to reread a book to get the most from it. Of course, as you are a routine rereader, Kevin, and you don’t think the second part holds up, then I could be mistaken on this one.

I read Jeff in Venice in proof copy from Canongate, and I mentioned in my review that the book has no fewer than seven epigraphs (two at the beginning, two at the start of part 1, two at the start of part 2, and one at the end). I had to edit my review to say that after seeing a finished copy in the shops, as the proof in fact contained ten epigraphs – 3, 3, 3 and 1 – which again, Dyer must have felt was too pretentious, or at least self-indulgent, even for him. I didn’t keep my proof so I wish I could see which ones he discarded. It might be enlightening.

LikeLike

April 11, 2009 at 11:52 pm |

I did find more to like in Part Two of Dvisadero on the second read, although I still would have preferred to see some of the very interesting aspects that were launched in Part One developed further. I was quite intrigued by all three characters and two of them disappear in Part Two. I did wonder if I had totally missed Ondaatje’s point on my first read and become too intrigued by the story and characters in Part One — the reread showed that wasn’t the case. If you ever get time to reread it, I’d be interest4ed in what your second impression is. I can understand what Michaels is trying to do with her separation (even if I don’t think she succeeds), Ondaatje still has me scratching my head. Who knows, that might be exactly what he intended.

LikeLike

April 12, 2009 at 10:06 pm |

I like your story about the launch. You do have to keep an eye on the blog. I have some posts that are still in the development stage, but because I forget to look at the posting dates, it’s published before I realize that I have done nothing for the post.

Thanks for including the references to this work. It helps to understand things. I am not an art historian, so every little bit helps.

Congrats on your blog-versary.

LikeLike

April 16, 2009 at 9:00 am |

So where should I start with Dyer? I’ve never read anything by him. John mentioned “commercial suicide”, and a book called Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi is a little bit uniniviting. I also read a Sunday Times review that gives it a stinging dismissal.

I’m guessing it perhaps isn’t Dyer’s best.

LikeLike

April 16, 2009 at 3:41 pm |

Thanks ever so much for that link, Jonathan — what an incredibly bitchy review. The former journalist in me can’t help but think that since the Telegraph has proclaimed Dyer “quite possibly the best living writer in Britain” (I like him but even I find that a bit much), the Times has decided they need to supply some equally inaccurate ballast. I know from experience how incredibly venomous a small, self-contained world like the book-reviewing one can be. There are days when the ex-journalist in me regrets that we no-cost bloggers are steadily but surely putting paid reviewers out of work — and then a dreadful, useless review like this comes along and I realize that it is for the best. For a more useful critical assessment, you might want to check out James Wood in the current edition of the New Yorker review here. Wood also offers a worthwhile comparison between the work Dyer calls fiction and non-fiction.

I don’t think Dyer is perfect but I do like him a lot I can understand those who would not like him — there is a breeziness and flippancy to his writing that I find quite entrancing, but others would find lazy. I am a bad person to advise on where to start as I have only read the two novels reviewed on this blog (Jeff and Paris Trance). I know John Self thinks the work Dyer calls non-fiction is better and I have ordered a couple of volumes (But Beautiful, his portraits of jazz musicians, and Out of Sheer Rage, his non-biography of D. H. Lawrence) to see what I think. I am guessing that Dyer is best first approached from whatever genre most attracts you (in my case, fiction). I think his strength is the way that he does overlap genres (fiction, criticism, biography, travel writing) — he isn’t best at any one of them, the beauty is in the mix (this totally escaped the Times reviewer, but then I think he was working to a different brief than truly evaluating the work). If that prospect doesn’t appeal to you, you might want to give him a miss completely — I’m certainly glad I found him.

LikeLike